And now for something completely different. (Well, not quite…)

It seems that I’ve been blogging about COVID-19 on this blog almost nonstop without (much) interruption for close to the last 16 months because, well, I have. Starting with what in retrospect seems like an overly optimistic post about the World Health Organizations official declaration on March 11, 2020 that the epidemic of disease due to the then-novel coronavirus had become a pandemic, followed by then-President Trump’s declaration of a national emergency, it seems that my output on this blog has been almost all COVID-19 all the time. True, I’m not the only one, but at least much of the rest of the crew covered other topics more often than I have. Be it conspiracy theories, doctors behaving badly (as they did throughout the pandemic), “wonder drugs” for COVID-19 like hydroxychloroquine or ivermectin, or antivaccine lies about the new COVID-19 vaccines that have led wealthy countries (like the US) to get out from under the worst of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been my niche. I could use a break.

That’s why I thank Scott Gavura for sending me this week’s topic. I’m sure I’ll soon be back to more information, disinformation, science, and pseudoscience regarding COVID-19, as the pandemic isn’t over yet. The report I’m about to discuss, however, allows me to follow up on a favorite topic of ours here at SBM, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), which before its “rebranding” a few years ago was formerly known as the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). I’m referring, of course, to the NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021–2025, which, having apparently been published last month (which I should have noticed), must have been a bit late due to the pandemic, given that one would expect a strategic plan set to begin in fiscal year 2021 to be published before that fiscal year started in October 2020. I figure, though, that if NCCIH can be a bit late with its latest five year strategic plan, then I can be several weeks late writing about it.

The illustrious history of NCCIH five year strategic plans

Regular readers of SBM know that we are not a fan of this particular Center in the NIH. The reasons are many and have been documented extensively going back to the very beginning of this blog. (Just use the search function for “NCCAM” or “NCCIH” for copious examples.) As you might recall at the time of the founding of the Office of Alternative Medicine in 1991, a relatively tiny office that would later “evolve” into NCCAM and then NCCIH, physicians and scientists at the NIH were not exactly clamoring for a center to study quackery to see if any of it worked. Rather, it was forced on the NIH by Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA). Longtime readers know how NCCAM really came about. One wonders if Rothenberg Gritz ever came across the late, great Wally Sampson’s classic 2002 article, “Why the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) Should Be Defunded” or the now retired (and dearly missed) Kimball Atwood’s “The Ongoing Problem with the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine“. Even if you buy into the false notion that NCCIH (née NCCAM) has completely reformed itself and doesn’t study or promote quackery any more, a history lesson is important. What really happened matters. I went into the details of the story six years ago, but I think it’s worth it right here to do a brief recap before I delve into the latest strategic plan.

Basically, Sen. Tom Harkin was a believer in a lot of alternative medicine and had claimed that bee pollen had cured his allergies. He learned of bee pollen from two constituents, Berkley Bedell and Frank Wiewel. Bedell believed in colostrum to treat “chronic Lyme disease” and that his prostate cancer had been cured by an alternative treatment called 714-X (which was derived from camphor), while Weiwel was a champion of immunoaugmentative therapy for cancer, which was a mixture of blood sera. Bedell introduced Harkin to Royden Brown, a promoter of High Desert bee pollen capsules. Persuaded by Brown to take 250 bee pollen capsules within five days, he rejoiced that his allergies had seemingly disappeared.

It soon became clear that the OAM was not intended to rigorously study alternative medicine, but rather to provide a seemingly scientific rationale to promote it. The office was initially set up with an acting director and an ad hoc panel of twenty members, many of whom Harkin hand-picked, including advocates of acupuncture, energy medicine, homeopathy, Ayurvedic medicine, and several varieties of alternative cancer treatments. Deepak Chopra and Bernard Siegel were also included. Critics of quackery were consulted and considered for panel membership, but—surprise, surprise!—none not selected. These pro-alt med panel members became known in the OAM as “Harkinites”. Much of the history of the NCCAM, back when it was the OAM in the 1990s and then after it was renamed NCCAM, consisted of battles between directors of the organization, who were trying to be scientifically rigorous, and the Harkinites, who had veto power over much of what the new center could do. In fact, even though Sen. Harkin retired at the end of 2014, his influence lives on in that the National Advisory Council for Complementary and Integrative Health (NACCIH), the committee that oversees NCCIH and to which the NCCIH director answers, includes naturopaths, acupuncturists, and chiropractors, among other quacks on its roster.

Also, I can’t help but point out that in 2009 Sen. Harkin bemoaned what NCCAM had accomplished:

One of the purposes of this center was to investigate and validate alternative approaches. Quite frankly, I must say publicly that it has fallen short. It think quite frankly that in this center and in the office previously before it, most of its focus has been on disproving things rather than seeking out and approving.

That was basically saying the quiet part out loud. As Dr. Peter Lipson put it:

Well, at least he’s honest. He comes right out and bemoans the fact that science hasn’t upheld his quasi-religious medical beliefs. He just doesn’t get it. If you choose to investigate a scientific question, you have to be prepared for “bad news”. You don’t get to decide the outcome before the fact.

Indeed. But Sen. Harkin went beyond that:

It is time to end the discrimination against alternative health care practices.

It is time for America’s health care system to emphasize coordination and continuity of care, patient-centeredness, and prevention.

And it is time to adopt an integrative approach that takes advantage of the very best scientifically based medicines and therapies, whether conventional or alternative.

This has been the mission of NCCIH since Sen. Harkin set up its predecessor 30 years ago. Its mission has never been to determine if “unconventional” and “alternative” treatments work, but rather to assume they do work and look for evidence to support “ending the discrimination” against them.

Meet the new Director, not quite the same as the old Director?

There’s an interesting twist now, too, which is one reason why I was more interested in this strategic plan than the last one. The NCCIH has a (relatively new) director, and this is her first five year strategic plan. Say what you will about Dr. Josephine Briggs, who retired in 2018, she was a real scientist, so much so that I not infrequently wondered how she had been roped into becoming director of the NCCIH. You might even recall, that Steve Novella, Kimball Atwood, and I even met with her back in 2010. On the other hand, even Dr. Briggs was prone to making credulous speeches about the glories of “integrative medicine” to naturopaths.

In any event, the woman appointed to replace Dr. Briggs as director in 2018 is Dr. Helene Langevin. Her background is very different from that of her predecessor Dr. Briggs, who was a nephrologist with impeccable scientific credentials at the time of her initial appointment (much to the frustration and consternation of some advocates). Indeed, Dr. Briggs was an interesting and odd choice because she had no background in “integrative medicine” and had not used CAM in her practice or done any research into it. I suspect that, at the time, she was probably intended as a director to impose some scientific rigor to NCCAM, although I also wondered how she could have met with the approval of NACCIH. Be that as it may, although I had my disagreements with Dr. Briggs over the years, most derived from my view that what NCCIH was studying consisted of pseudoscience and quackery and that the interventions that it was studying that weren’t pseudoscience and quackery were well within the realm of SBM. It’s what I refer to as the “rebranding” of modalities like diet, exercise, and lifestyle as being somehow “alternative”. Even so, I gave Dr. Briggs some credit because I thought she was in an impossible situation. She was a real scientist trying to impose scientific rigor on an enterprise that was, by its very design, resistant to rigorous science. That she largely failed is probably not her fault; it was an impossible task.

Dr. Langevin, on the other hand, has fit right into the culture at NCCIH, because she is a true believer. In brief, Langevin has been studying acupuncture ever since at least the 1990s, when she came up with the idea that somehow the needle interacting with the connective tissue is how acupuncture “works”. Of course, nowhere in her “research” have I been ever able to see anything resembling a coherent or even suggestive mechanism as to how connective tissue could modulate the “activity” of acupuncture. Also, to her it’s not just the needles, but the twirling of the needles that is so important to do…something. Somehow this minute stretching of the tissue is enough to explain acupuncture’s miraculous “effects.” It’s not quite clear. She also seems unduly impressed by ultrasound findings in patients with chronic low back pain suggesting more thickened tissue, as though chronic inflammation might be going on. Ya think? What could sticking little needles into the body do for this? It doesn’t even make sense.

The first time I ever encountered Dr. Langevin was when I considered a study that she published in 2010, in which she used all sorts of statistical models looking for associations between differences in impedance and meridians and correlations between differences in impedance and ultrasound-measured tissue density. Her team claimed to have found a small difference in impedance between the Large Intestine meridian impedance and the control, while all other comparisons were was negative. Did it mean anything? All I could come up with is that there might be a difference in impedance between one area on the upper arm and another area. She’s also published a number of other studies looking for correlations between the density of fascia (the connective tissue lining muscles) and acupuncture points. It’s basically been quackademic medicine at its…not finest.

As I said, she fits right in. So what does her first five year strategic plan say?

Meet the new plan, same as the old plans?

Since I’ve written about the 2011-2015 and 2016-2021 NCCIH strategic plans, I thought it would be fun to list their key strategic objectives first, as a bit of history against which to compare the key bullet points of the 2021-2025 strategic plan.

The 2011-2015 (then-)NCCAM Strategic Plan included three main goals:

- Advance the science and practice of symptom management.

- Develop effective, practical, personalized strategies for promoting health and well-being.

- Enable better evidence-based decision making regarding CAM use and its integration into health care and health promotion.

NCCAM proposed five strategic objectives through which to achieve these goals.

- Advance Research on Mind and Body Interventions, Practices, and Disciplines

- Advance Research on CAM Natural Products

- Increase Understanding of “Real-World” Patterns and Outcomes of CAM Use and Its Integration Into Health Care and Health Promotion

- Improve the Capacity of the Field To Carry Out Rigorous Research

- Develop and Disseminate Objective, Evidence-Based Information on CAM Interventions

At the time, I couldn’t help but note that research into natural products is already a subdiscipline of the science of pharmacology known as pharmacognosy and that “real world” patterns and outcomes struck me as code for avoiding having to do rigorous double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials to test whether any of the quackery being studied has any effect detectable above sham or placebo. That was just me. Let’s fast forward five years.

The 2016-2021 NCCIH Strategic Plan didn’t include overarching goals, sticking to five strategic objectives. At the time, I sarcastically referred to the plan as “Let’s do some real science for a change!” I think you’ll see why fairly quickly. Here are the five objectives:

- Advance Fundamental Science and Methods Development

- Improve Care for Hard-to-Manage Symptoms

- Foster Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- Enhance the Complementary and Integrative Health Research Workforce (cross-cutting)

- Disseminate Objective Evidence-based Information on Complementary and Integrative Health Interventions (cross-cutting)

Unsurprisingly, given the way that “integrative medicine” proponents have been “rebranding” quackery like acupuncture as “nonpharmacological treatments for pain“, pain was at the top of the scientific priority list:

- Nonpharmacologic Management of Pain

- Neurobiological Effects and Mechanisms

- Innovative Approaches for Establishing Biological Signatures of Natural Products

- Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Across the Lifespan

- Clinical Trials Utilizing Innovative Study Designs to Assess Complementary Health Approaches and Their Integration into Health Care

- Communications Strategies and Tools to Enhance Scientific Literacy and Understanding of Clinical Research

In 2016, I couldn’t help but notice the similarity between this plan and its predecessor, at least in outline. For instance, Objectives 1 and 4 in the new plan are little more than a repackaging of Objective 4 in the old plan, all of which carry with them an implicit admission of how poor the science carried out by NCCIH-funded investigators has been over the years. Indeed, one of the sub-objectives of Objective 1 was to “Develop new and improved research methods and tools for conducting rigorous studies of complementary health approaches and their integration into health care.” Objective 5 was even more similar in both plans; the two even have almost identical wording. Meanwhile, Objective 3 in the old plan was basically the same as one of the scientific priorities, namely “Clinical Trials Utilizing Innovative Study Designs to Assess Complementary Health Approaches and Their Integration into Health Care”. Of course, just as “real world outcomes” is code in NCCIH-speak for doing less rigorous “pragmatic” studies of various health interventions, whenever you see any sort of discussion of “innovative study design” with respect to “integrative” modalities, it almost always means “coming up with study designs that make it look as though this quackery actually works”.

Of course, as I said at the time, there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with a new five year plan strongly resembling the previous five-year plan. Such similarities do, however, make one wonder what progress has been made on the objectives shared by both plans and whether something new needs to be done to meet those objectives. Let’s see what we get with the 2021-2025 NCCIH Strategic Plan.

“Mapping a Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health”?

The subtitle of the plan is “Mapping a Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health“. I mention that right off the bat because it is a favorite trope of proponents of “integrative medicine” or “integrative health” (or, as I like to put it, “integrating” quackery with science-based medicine) that somehow “integrative health” is all about taking care of the “whole person” in a way that “conventional” medicine cannot or will not. I sense in this the influence of the new NCCIH director. If you read the previous two strategic plans, you’ll see a more conventional scientific approach, even if certain commonalities were there, including an emphasis on “innovative” or “real world” (i.e., less rigorous) study designs that provide a better chance of results that appear to support placebo interventions like acupuncture.

Dr. Langevin even lays it out right in her director’s message, which I will quote rather extensively here, noting that, as Dr. Briggs invoked the opioid addiction epidemic five years ago, Dr. Langevin invokes the COVID-19 pandemic of the last year and a half, noting that we have “witnessed the dire consequences” of chronic disease “during the COVID-19 pandemic, which illustrates how chronic underlying conditions pose immediate and long-term risks to those infected” before launching into this justification:

Now, more than ever, we need to look at the multiple factors that promote either health or disease and scientifically consider the whole person as a complex system in which health and disease are part of a bidirectional continuum. Our current biomedical research model is superb in advancing the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of organ-specific diseases with growing precision. This knowledge is based on an increasingly sophisticated understanding of pathogenesis, or the mechanisms by which diseases occur. On the other hand, health restoration through self-care, lifestyle, or behavioral interventions is much less studied. Examples of health restoration, or “salutogenesis,” would be the return to health after an acute viral illness or flareup of a chronic condition; normalization of cholesterol, hemoglobin A1C, and/or blood pressure in a patient with metabolic syndrome through lifestyle modification; and return to function and mobility following a musculoskeletal injury. We currently do not know whether salutogenesis consists of “pathogenesis in reverse” or whether it requires some specific salutogenic or healing pathways to be engaged to bring an individual back toward health. Unlike the treatment of disease with drugs that target specific molecular pathways, health restoration through salutogenesis is likely complex and multifactorial and involves the whole person. Advancing research on whole person health will support the investigation of nondrug and noninvasive approaches to improve and restore health.

Meeting this challenge is right up our alley. By its nature, the mission of NCCIH includes both integration and health. NCCIH was created more than 20 years ago to facilitate the study and evaluation of complementary and alternative medical practices and to disseminate the resulting information to the public. Over time, we incorporated a focus on integrative health research to bring conventional and complementary approaches together in a safe, coordinated way with the goal of improving clinical care for patients, promoting health, and preventing disease. Now, we are expanding our definition of integrative health to include whole person health, or empowering individuals, families, communities, and populations to improve their health in multiple interconnected domains: biological, behavioral, social, and environmental. This strategic plan, built on the foundation NCCIH has fostered for two decades, continues to advance our mission through an effort to better define and map a path to whole person health.

My first thought was that by embracing complexity in the name of “whole person health,” whether Dr. Langevin realizes it or not, she’s making it easier to seem to demonstrate that ineffective treatments work. She’s also embracing a research model that would deemphasize nasty, reductionist things like randomized controlled clinical trials, all in the name of embracing “whole person” or “holistic” health, while she doubles down on common tropes in quackery:

And with the goal of improving and restoring health rather than just treating disease, we offer strategies to foster research on health promotion and restoration, resilience, disease prevention, and symptom management. As always, we remain committed to enhancing the complementary and integrative health research workforce and disseminating what we learn.

I hate this commonly asserted false dichotomy with a passion, the claim that “conventional medicine” only “just treats disease” while “integrative medicine” is so much better than that because it is about “improving and restoring health”. I don’t recall Dr. Briggs stating this false dichotomy so brazenly, but, then, she was a real scientist and a bit of a fish out of water at NCCIH.

The false dichotomy gets even more irritating in the Introduction, specifically the section entitled “Building a Path to Whole Person Health“. First, there’s another common trope:

The concept of whole person health will continue to evolve, just as the concept of complementary medicine has changed over time as the line between conventional and complementary medicine has increasingly become blurred.

The reason this line has become “blurred” is not because woo works. It’s because “integrative medicine” advocates have been so successful at rebranding lifestyle interventions that have long been part of science-based medicine, such as nutrition and exercise, as somehow first “alternative”, then “complementary”, and now “integrative”, and then combining them with quackery like naturopathy, huge swaths of traditional Chinese medicine, and the like.

Here comes the doubling down:

Any kind of knowledge base includes both analysis and synthesis: analysis breaks things down into individual components, and synthesis puts them back together to understand the whole. For more than a century, biomedicine has been strongly pulled toward analysis, from its early organization into organ systems in the late nineteenth century to cellular and molecular biology with its increasingly detailed understanding of cells, molecules, genetics, and signaling pathways. In the last few decades, systems biology, derived from ecology, has begun to influence biomedical research, with a greater awareness of how body systems relate to one another and how networks of genes influence physiological processes. Nevertheless, our predominantly biochemical approach to treatment remains overwhelmingly pharmacologic. And because we tend to think about a specific disease or specific organ system, even when co-occurring conditions are present, we typically treat them separately, sometimes with medications that interfere with one another.

Now is the time for biomedical science to work toward restoring its balance between analysis and synthesis. We can do this by strengthening our efforts toward integration of knowledge across disciplines, focusing on the whole person, and taking a transdisciplinary approach that integrates the natural, social, and health sciences and transcends traditional boundaries.

Notice the very old trope beloved of quacks everywhere, namely the disparagement of “reductionist” science, compared to—of course!—the quacks, who supposedly are the only ones to take care of the “whole person” and, conveniently enough, “treat the causes” instead of the symptoms of disease. (I have a hard time not mentioning that homeopathy was invented to treat symptoms, not causes, but that’s just me.) Moreover, even though there might be a germ of truth to this, I would argue that it was more due to the limitations of basic scientific techniques than anything else. These days, with the rise of genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and various flavors of systems biology, “conventional” science is getting very good at studying not just whole organs, but the whole person.

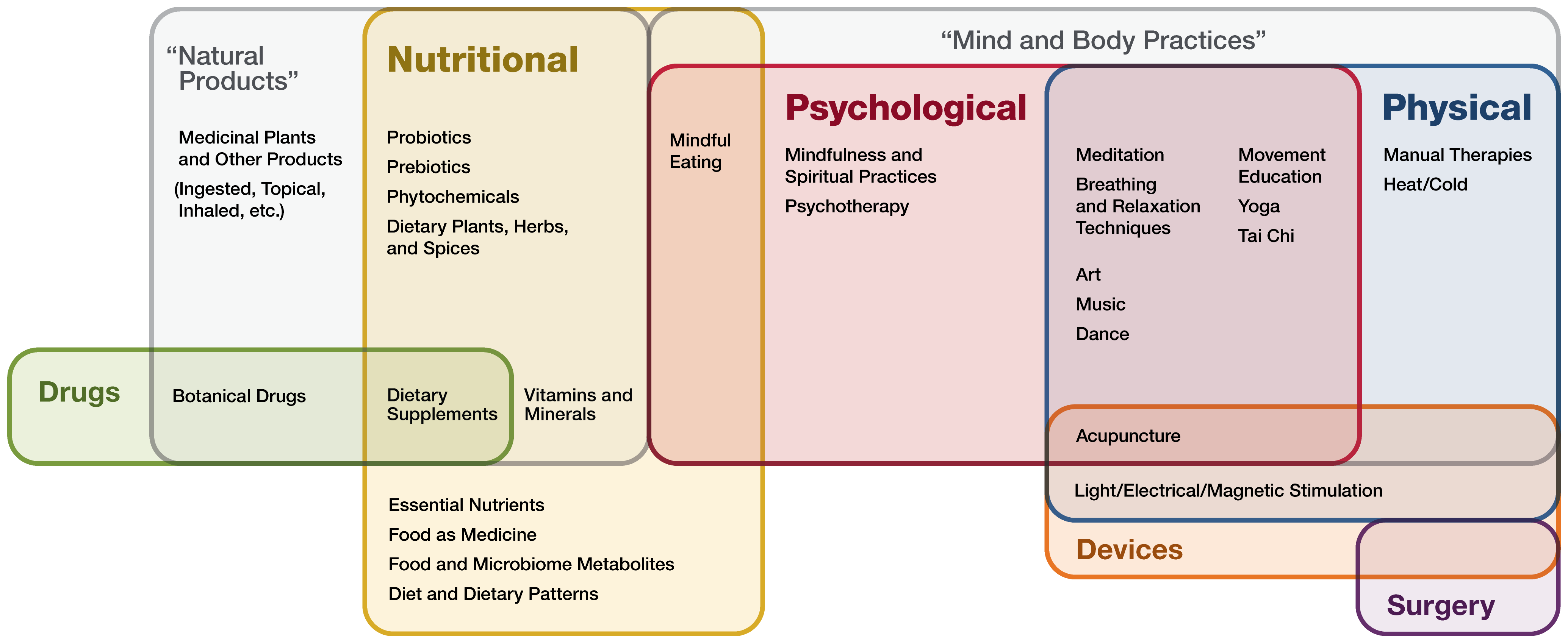

The real meat of the “reframing” that Dr. Langevin is pushing, though, is in the next section of the introduction, “Reframing How We Think About Natural Products and Mind and Body Practices“. Instead of all those previous categorizations of “alternative,” “complementary,” or “integrative therapies” (such as mind-body, herbal/natural products, “energy medicine”), we now get just three: nutritional, psychological, and physical.

But it’s more than that:

To ensure continuity, the Center is not abandoning its mind and body practices and natural products terminology or research but is recategorizing the approaches that fall within our research mission based on their primary therapeutic input. This categorization illustrates where there are partially overlapping boundaries, including with pharmacologic drugs and devices. For example, a single natural product can be available as a food or food component, dietary supplement, or medication (e.g., niacin). Foods, probiotics, and dietary supplements, such as fish oil, are often used as part of a healthy diet and are also frequently recommended by practitioners. Mind and body practices, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, can overlap with more conventional practices like psychotherapy. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy increasingly incorporates relaxation, meditation, and other modalities.

And, guess what? This is just like “conventional” therapies:

There are both conventional and complementary examples of multicomponent interventions. Conventional cardiac rehabilitation often includes nutritional recommendations, exercise, and a psychological component such as mindfulness-based stress reduction. Tai chi is also increasingly being incorporated into these programs. Although this example illustrates a holistic approach that recognizes interconnectedness of the psychological and physical components, the diagnostic and therapeutic framework under which these combined therapies are used is that of conventional medicine. In contrast, other types of multicomponent therapeutic interventions or systems bring together different modalities using diagnostic and/or therapeutic frameworks that are different from those of conventional medicine. For example, traditional Chinese medicine includes nutritional components like herbs and physical components like tai chi, soft tissue manipulation, and acupuncture. The difference between traditional Chinese medicine and conventional cardiac rehabilitation is that the framework that ties each intervention together in traditional Chinese medicine is distinct from those of conventional medicine. It is important to address this from a research perspective to gain more insight into whole person health.

It is true that there are multimodality treatments in “conventional” medicine. It’s even true that we combine dietary recommendations with exercise and, when appropriate, pharmacologic interventions. The treatments for heart disease and type 2 diabetes are but two examples. Here’s the difference that reveals what Dr. Langevin’s game is. In “conventional” medicine, the diagnoses are based on science, as are the “framework” that ties the interventions together in multimodality treatments. The contrast with, for instance, traditional Chinese medicine couldn’t be more obvious, even though this report is asserting that TCM is more “holistic.”

This is a narrative that we hear time and time and time again about TCM, that it considers the “whole patient,” that it is “wholistic”, that it considers the patient as a “system”. Of course, if that “system” isn’t based on science and evidence, then who cares? After all, what about ancient “European” medicine, which stated that imbalances in the four humors (phlegm, blood, yellow bile, and black bile) caused disease? It’s pretty similar in many ways to TCM postulates, which ascribes illness to six pernicious influences. These include wind, cold, heat, dampness, dryness and summer heat, which are, like totally not like the four humors. (There are, after all, six pernicious influences. Can’t you count?) TCM also has the “five elements” (fire, wood, earth, water, and metal), which are associated with different organs. So maybe TCM is on to something because its prescientific belief is a bit more complicated than the prescientific belief system that undergirded “Western medicine” for many centuries before scientific medicine arose. That means TCM must be better, right? After all, there must be a reason why there’s all this scientific interest in studying diagnoses based on the five elements and six pernicious influences, but no love left over for studying diagnoses based on imbalances between the four humors, right?

I know, I know. This is a comparison I’ve made many times.

Five more objectives, five more years

With the introduction out of the way, let’s look at the five objectives in this strategic plan. They will sound familiar, but not entirely:

- Objective 1: Advance Fundamental Science and Methods Development

- Objective 2: Advance Research on the Whole Person and on the Integration of Complementary and Conventional Care

- Objective 3: Foster Research on Health Promotion and Restoration, Resilience, Disease Prevention, and Symptom Management

- Objective 4: Enhance the Complementary and Integrative Health Research Workforce

- Objective 5: Provide Objective, Evidence-Based Information on Complementary and Integrative Health Interventions

Objectives 4 and 5 seem to appear in pretty much every NCCIH strategic plan in one form or another. In fact, Objective 5 has appeared in almost the same wording since the 2011-2015 plan, complete the part about “objective, evidence-based information.” Similarly, so does some variation on Objective 1, which, as I mentioned before, I like to refer to as “Let’s do some real science for a change!” Come to think of it, Objective 3 just combines Objectives 2 and 3 from the last strategic plan, combining symptom management with health promotion and adding “restoration and resilience” to the mix, because “resilience” is the latest hot term.

That leaves Objective 2 doing the heavy lifting. This is where Dr. Langevin, true believer that she is in acupuncture, appears to be starting to make her mark on NCCIH. This objective has four strategies:

- Strategy 1: Promote basic and translational research to study how physiological systems interact with each other.

- Strategy 2: Conduct clinical and translational research on multicomponent interventions, and study the impact of these interventions on multiple physiological systems (e.g., nervous, gastrointestinal, and immune systems) and domains (e.g., biological, behavioral, social, environmental).

- Strategy 3: Foster multicomponent intervention research that focuses on improving health outcomes.

- Strategy 4: Conduct studies in real world settings, where interventions are routinely delivered, to test the integration of complementary approaches into health care.

Let’s dispense with Strategy 4 first. It’s the same old, same old. Basically “real world” settings is code for doing so-called “pragmatic trials”. I’ve discussed the problem with this many times, as has Steve. There is one requirement for a pragmatic trial. That requirement is that the novel modality being tested against standard-of-care must already have been demonstrated to work in randomized clinical trials. As much as, for example, acupuncture aficionados like Dr. Langevin like to try to claim that acupuncture has been shown to work for the various health issues for which it is used, in reality when you look closely it’s not hard to see that the studies are most consistent with acupuncture “working” through placebo effects, not through any specific physiologic effect. As I like to say when discussing acupuncture studies, doing pragmatic studies on “integrative” interventions of the sort under consideration at NCCIH is putting the cart before the horse.

Come to think of it, I’ll just dispense with Strategy 1 as well, which is, at its heart, no different than what the various disciplines falling under systems biology are already doing—and have been doing for the last couple of decades, at least. It’s also the sort of thing best left to scientists who don’t believe in magic, as well.

I must admit that I laughed out loud when I read this part of Strategy 2:

NCCIH hopes to expand research on integrated multicomponent therapies. One challenge in clinical research on complex interventions is that researchers may want to tailor the interventions to specific populations, study individual components, or change the intervention to make it more convenient, but these modifications may make replication difficult and reduce the effect size of the intervention. It is important to have a reproducible intervention or algorithm of care that can be consistently delivered by different clinicians at different sites to conduct multisite trials to assess efficacy or effectiveness of the multicomponent intervention. Another challenge is how to power a study for multiple primary outcomes. NCCIH is also interested in the development of innovative strategies to evaluate multiple outcomes in a single trial.

So NCCIH wants to study multi-modality, multistep treatments and look at multiple outcomes in a single trial! What could possibly go wrong? Here’s a hint: The more outcomes you look at in a single trial, the harder it is to power the trial to determine if a difference in one of these outcomes between control and intervention is significant, as the problem of multiple comparisons comes into play. As you might recall, the more comparisons you make, the greater the chance of one or more of them producing a “statistically significant” difference by random chance alone. That problem has to be taken into account, which usually means more subjects, often a lot more. In fairness, I will give NCCIH credit for one thing. That part about having a “reproducible intervention or algorithm of care” sounds suspiciously like standardization, which is usually anathema to quacks, who love to tout how they “personalize” their interventions to the individual patient.

As for Strategy 3, well:

There is a fundamental lack of translational research on the mechanisms of resilience and health restoration in humans. In particular, the mechanisms of nutritional, psychological, and physical interventions in restoring health after an acute illness or recovery from a chronic condition are an understudied area that needs a multisystem approach to identify mechanisms and predictive biomarkers that could be used to optimize their effects. NCCIH seeks to support research that could expand the mechanistic and evidence base on complementary health approaches for preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders and for promoting psychological and physical health, resilience, and health restoration.

This is another example of the “rebranding” that “integrative health” proponents are so slick at. At its core, Strategy 3 is little different from what scientists and physicians are already doing in terms of research into combining different modalities. The difference is, of course, that NCCIH will include prescientific systems of medicine, such as TCM and Ayurveda and quack modalities of naturopathy (which always includes The One Quackery To Rule Them All, homeopathy), chiropractic, and osteopathy, none of which are based on a scientific understanding of the human body and its biology, disease, and pathophysiology. It says so right in the part of the introduction that describes the vision of NCCIH:

NCCIH supports research on a diverse group of nondrug and noninvasive health practices encompassing nutritional, psychological, and physical approaches that may have originated outside of conventional medicine, many of which are gradually being integrated into mainstream health care. These include natural products, such as dietary supplements, plant-based products, and probiotics, as well as mind and body approaches, such as yoga, massage therapy, meditation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, spinal/joint manipulation, and acupuncture. In clinical practice, these approaches are often combined into multicomponent therapeutic systems, such as traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, chiropractic, osteopathy, and naturopathy, that have distinctive underlying diagnostic and theoretical frameworks. Integrative health care seeks to bring conventional and complementary approaches together in a safe, coordinated way with the goal of improving clinical care for patients, restoring health, promoting resilience, and preventing disease.

This description of NCCIH’s mission and vision gives the game away, as does the emphasis on “biomarkers” of response to…quackery. So does this image:

Notice how there’s little mention of specific modalities, at least compared to past emphases. Everything has been subsumed into one of three areas: nutritional, psychological, and physical. Notice how surgery is included under the category of “mind and body practices,” along with acupuncture, because, you know, they’re both basically the same.

Meet the new plan, same as the old plan…?

As you can see, much of the new NCCIH strategic plan is more or less the same as the old NCCIH strategic plan. All the usual areas are emphasized, but Dr. Langevin cleverly combined two Objectives into one and then added what was clearly her own: Advance Research on the Whole Person and on the Integration of Complementary and Conventional Care. It’s actually rather brilliant, if your objective is to make quackery seem equivalent to science-based care. Add a bunch of complexity to the interventions being studied by “studying” them as “systems” and then “study” the “interactions” between them on multiple outcomes. It’s a strategy that’s guaranteed to produce some seemingly “positive” results.

The new plan is the same as old plans, and then some. It’s smarter in that it hides the quackery, something the last plan did, but in a cleverer way. Sadly, NCCIH appears to be back and poised to be as quacky as ever.